Newsletter 11 - AI's Rulebook Emerges: Deciphering Regulatory Realms and Policy Pioneers

Making sense of emerging AI regulation across the world and its implications

Have you ever felt overwhelmed by the rapid advancements in AI, struggling to discern between hype and reality? This year, the AI landscape has transformed dramatically, presenting both extraordinary potential and complex challenges. Navigating this evolving terrain requires more than just keeping pace; it demands a structured approach to understand and contextualize the deluge of information. I've created a framework that simplifies the complexity of AI, offering clear insights into its inherent definitions, external constraints, and impactful applications.

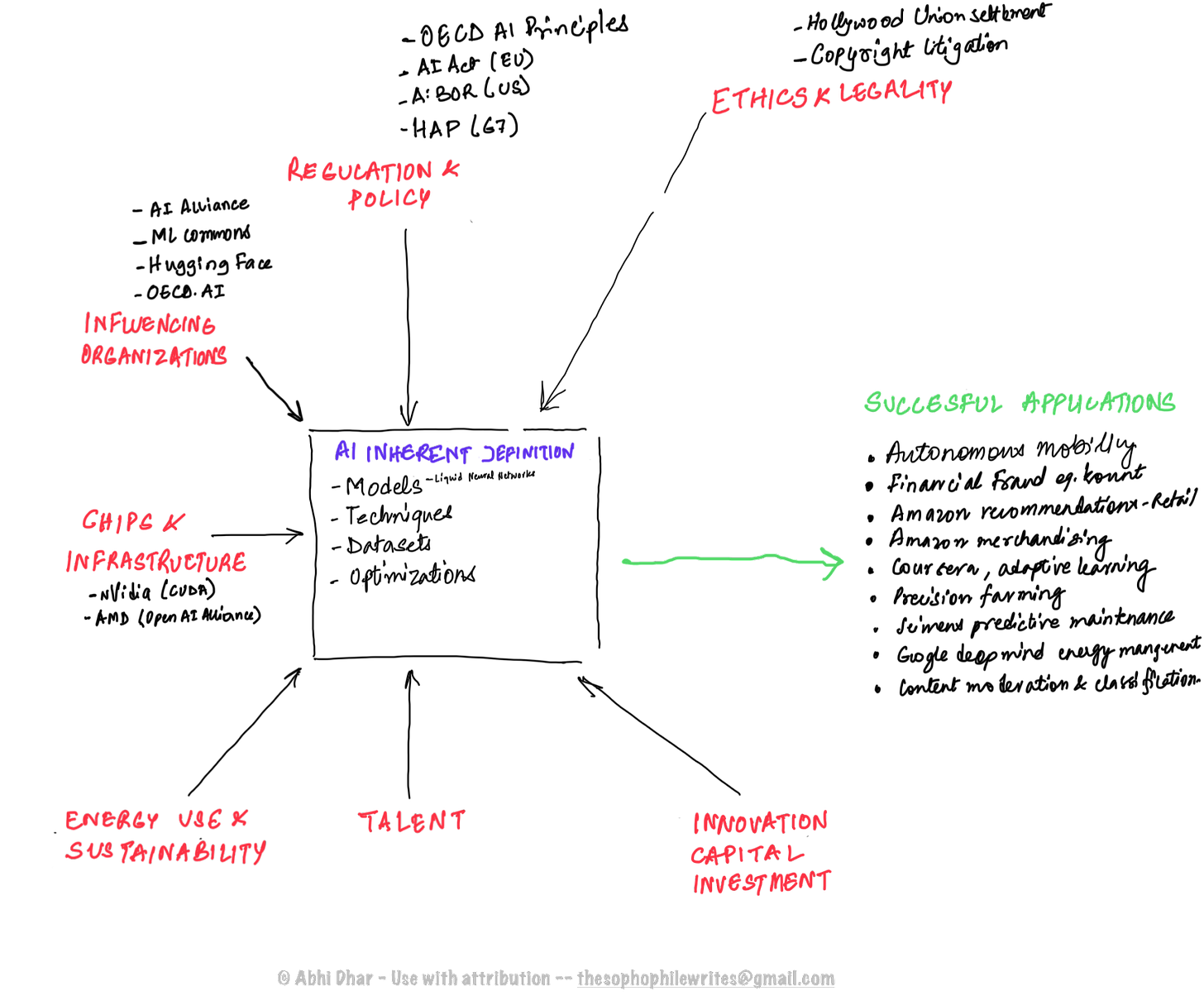

A simplifying framework to make sense of everything happening in and around AI

In my framework I use three main notions, the first is the “Inherent Definition of AI” which includes all the advancements in models, architectures, data, techniques and optimizations. Second are the externalities or constraints affecting AI; things like Regulations, the Organizations influencing it, Talent, Chips and Infrastructure, Energy Implications and Capital Investment happenings. Finally I look at the successful applications that are creating commercial and societal value as the primary indicator of demand for this technology.

I like to think of it this way: successful applications provide the impetus to improve the technology and all of its attributes so as to make it increasingly lucrative. However, the gating factors or supply constraints control or modulate the progress of the overall ecosystem. It's the interplay between the inherent technical advancement, the constraints and, the pull of successful application that will drive the iteration and improvement of these technologies.

My framework is hand-drawn, not generated by AI.

In subsequent editions, I will refer back to this framework to put the topic I am talking about in context. If I find a new facet or attribute in the information that I receive, I will adjust the framework.

Policy and Regulatory perspectives are becoming real and rapidly getting adopted

This time I want to focus on the regulatory implications and developments in various countries and bodies across the world to get ahead of widespread AI use.

As the potential of AI started becoming clearer, the various policy and regulatory bodies across the world increasingly felt the need to get involved and ensure that the use of AI was mitigated for any risk to citizenry and also guided for use in advancing humanity. In my newsletter 10, I described how there is a real philosophical debate around the notion of “Effective Altruism”, a dynamic in how the various AI platform companies are approaching their work and managing their talent. This notion of fair use and advancement of humanity, trustworthiness and transparency is becoming a key theme in the work that policy makers and regulators are publishing across the world. At the same time the enormous commercial value that can be generated is in direct conflict with such intentions. Therein lies the rub.

Before 2019, while many governments, such as the UK, Canada, and Japan, were discussing national AI strategies; there really wasn't a multinational policy framework that could be adopted and iterated upon. Even as the rest of the world was waking up to the potential of this technology, China was prescient and had started forming a national strategy to leapfrog the rest of the world.

China sees the future first, the rest of the world follows

In 2017, AlphaGo's victory over Ke Jie demonstrated the advanced capabilities of AI in Go, a game deeply ingrained in Chinese culture and considered more complex than chess. This was not just a technological triumph but also a symbolic one, showcasing the power of AI. Go is a game with deep historical and cultural significance in China, and AlphaGo's victory over a Chinese world champion was perceived as a challenge to China's intellectual and cultural heritage. This defeat in a quintessentially Chinese game was a matter of national pride and spurred a competitive response.

In July 2017, China's State Council released the "New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan." This policy aimed to make China the world leader in AI by 2030, with a domestic AI industry worth nearly $150 billion. The plan outlined objectives for AI integration in industries, military, and intelligent governance. China surpassed the US in the number of AI filings in 2017. Researchers in China claim they have developed the world's first AI capable of analyzing case files and charging people with crimes.

Since then we saw increased efforts in China to integrate AI in critical sectors like healthcare, education, and transportation. Major cities like Beijing and Shanghai began establishing AI development parks. The Chinese government significantly increased funding for AI research and development, focusing on core AI technologies and high-end chips crucial for machine learning. This has directly led to the constraints by the US on technology exports to China related to the chips that are used for AI model work.

By 2020, China introduced AI ethics guidelines, emphasizing responsible and ethical use of AI. The guidelines included principles on AI's harmonious coexistence with humans and the environment.

The OECD sets the tone for the rest of the world

Meanwhile in the rest of the world events started happening in quick succession. In 2019, the first multinational framework emerged. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is a policy organization focussed on sustainable growth with membership from Europe and North America. Starting in 2016 the OECD started working on principles and policies to govern the use of this technology. They realized that AI was a general-purpose technology, no single country or economic actor could tackle it's issues alone. They wanted to coordinate policy and regulatory response across the world for governing the use of AI based on international, multidisciplinary and multi-stakeholder cooperation. The intention was to ensure that the development and use of AI benefits people and the planet. In May 2019, the OECD AI Principles were adopted to “promote use of AI that is innovative and trustworthy and that respects human rights and democratic values”. Today one can go to OECD.AI which claims to be “a unique source for research, data and visualisations of AI trends and developments. It features a database of AI policies from almost 70 countries, a unique resource for governments to compare AI policy responses and share good practices.” The summary of key principles is below:

Inclusive Growth, Sustainable Development, and Well-Being: AI should benefit people and the planet by driving inclusive growth, sustainable development, and well-being.

Human-Centered Values and Fairness: AI systems should respect human rights, diversity, and democratic values. This includes ensuring fairness and non-discrimination.

Transparency and Explainability: There should be transparency and responsible disclosure around AI systems to ensure that people understand AI-based outcomes and can challenge them.

Robustness, Security, and Safety: AI systems must function in a robust, secure, and safe way throughout their life cycles and potential risks should be continually assessed and managed.

Accountability: Those responsible for AI systems should be accountable for their proper functioning in line with the above principles.

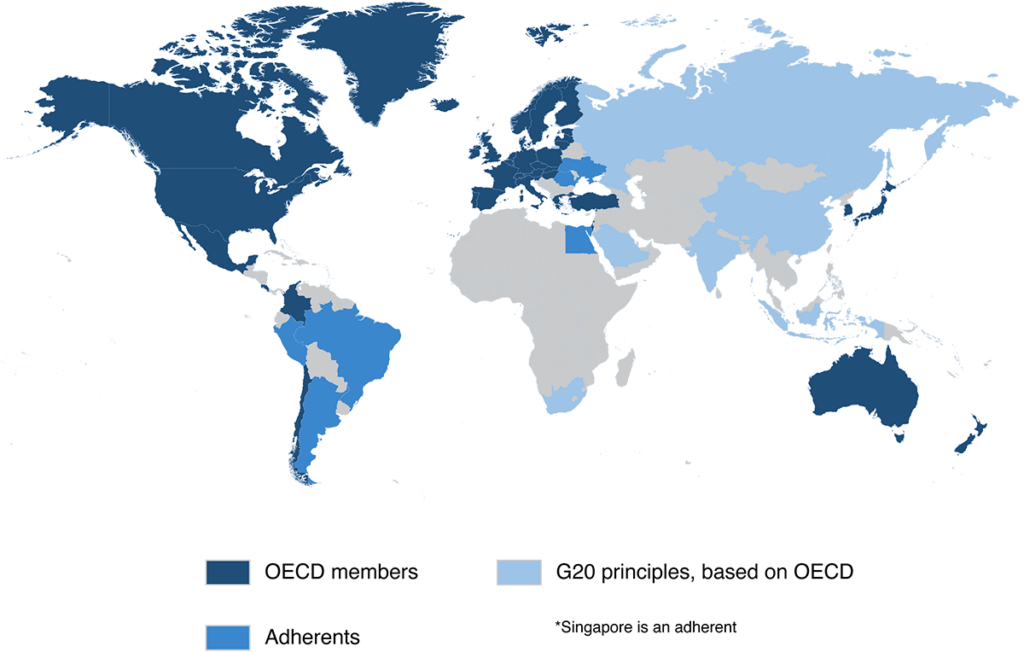

Later that year the G20 published their AI principles based on the OECD document. The G20's adoption means that these principles have been acknowledged and supported by a broader range of countries, including major emerging economies, thereby giving these principles a more global significance.

The world was burdened with the Covid pandemic so all of this news stayed off mainstream knowledge sharing. However as the world emerged from the pandemic news out of OpenAI and controversy around Google’s AI organization started raising the awareness and importance of this technology and the need for policy and regulation. Today some 70 countries have adopted or derived principles and policies based on the original OECD work. Here is a map showing its coverage from OECD.AI.

Source - OECD.AI

The Hiroshima AI process has the G7 doubling down on Gen AI

In May 2023 the G7 leaders met in Hiroshima and initiated a process to promote safe, secure, and trustworthy AI worldwide, focusing on "Generative AI". This process has four pillars. First, the process focuses on analysis of priority risks, challenges, and opportunities of generative AI. Second, it envisions a Code of Conduct for organizations developing advanced AI systems. Third, it seeks Project-based cooperation to address specific challenges and finally, it pursues Multi-stakeholder engagement with governments, academia, civil society, and the private sector.

In October 2023, G7 leaders endorsed the Hiroshima Process International Guiding Principles and set a deadline that by the end of 2023 they will develop a Hiroshima Process Comprehensive Policy Framework.

There are similarities with the OECD principles in that both emphasize the importance of responsible AI development and use, both involve international cooperation and multi-stakeholder engagement and both aim to address key risks and challenges associated with AI.

Where they differ is that the Hiroshima Process specifically focuses on generative AI, while the OECD AI Principles apply to all forms of AI. Also, the Hiroshima Process has a more complex structure, with multiple pillars and a Code of Conduct, while the OECD AI Principles focus on a single set of principles. Finally, the Hiroshima Process emphasizes the need for project-based cooperation, while the OECD AI Principles focus on guiding policy development.

There are several possible reasons why the G7 chose to launch the Hiroshima Process instead of building upon the existing OECD AI Principles adopted by the G20. The most obvious one is that they focus on Generative AI. It would appear that the G7 wanted to specifically address the unique risks and challenges associated with generative AI, which is capable of creating new content. Some argue that the G7 felt the OECD AI Principles lacked ambition and were not moving fast enough to address the rapidly evolving landscape of AI. The Hiroshima Process allowed them to take a more proactive approach and set their own agenda. It is also speculated that the G7 might have preferred to have greater control and ownership over the development and implementation of AI governance frameworks. By launching their own initiative, they were able to ensure that their specific priorities and concerns were addressed.

Finally there is the matter of appearances. The G7 might have also wanted to differentiate themselves from the G20, which includes emerging economies with different priorities and perspectives on AI governance. The Hiroshima Process allowed them to create a forum for like-minded countries to collaborate on this issue.

Launching a joint initiative like the Hiroshima Process helped the G7 to present a united front on AI governance and speak with one voice on the global stage. This could be especially important in negotiations with other countries and international organizations.

The US and the EU are diving in.

The OECD AI Principles act as a foundation, influencing both the US and EU approaches.

While the US Congress has been active in discussing AI it has not passed a comprehensive AI regulation whereas in The EU an AI Act has proposed regulation by the European Commission introduced in April 2021. This past week broad agreement on EU’s AI Act content has been achieved and it is expected to be law by 2025.

The EU AI Act categorizes AI systems based on their risk levels and sets legal requirements for high-risk AI systems. It emphasizes transparency, accountability, and adherence to fundamental rights. Once enacted, it will be one of the world's first major legal frameworks regulating AI, impacting AI development and use within the EU and for companies operating in EU markets.

In the US Congress various bills and discussions have occurred, focusing on aspects like research funding, national strategy for AI, and specific issues like facial recognition and AI in the workforce. While we wait for an actual bill to be passed by Congress, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy proposed a policy framework encompassing a set of guidelines in 2022. It focuses on protecting civil rights in the age of AI. It emphasizes the need for safe and effective AI systems, algorithmic discrimination protections, data privacy, notice and explanation about AI systems, and human alternatives to automated decisions. It guides federal agencies and lawmakers in the US on how to regulate and oversee AI development and use, ensuring AI systems don't infringe on citizens' rights. These agencies include the FTC, which has authority over “false and deceptive” practices such as AI deepfakes and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which is addressing potential bias of AI models in hiring processes.

The US AI Bill of Rights and the EU AI Act both align with the OECD’s emphasis on human-centric and trustworthy AI, but they differ in their legal authority and specific focus.

The US approach is a policy framework without binding legal force, focusing on civil rights protections. The EU AI Act is a legislative proposal with enforceable regulations, particularly for high-risk AI applications.

India sees the potential

An AI Task Force was constituted by the Indian Ministry of Commerce and Industry in 2017 to prepare India for the AI revolution. The task force submitted its report in 2018, providing recommendations to stimulate AI's growth in India. The NITI Aayog, a policy think tank of the Government of India, released a discussion paper titled "National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence" in June 2018. This paper laid the foundation for India's approach to AI, focusing on leveraging AI for inclusive growth and addressing the challenges in key sectors like healthcare, agriculture, education, smart cities and infrastructure, and smart mobility and transportation.

Having signed up to the G20 AI principles as a member (and in 2023 India held the presidency of the G20) it significantly influenced their approach. In budget speeches during 2019 till 2021, the Finance Minister of India announced various initiatives to promote AI, including the setting up of a National Centre for Artificial Intelligence and a national program on AI.

Are incumbents weaponizing regulation?

There is growing clamor around the thesis that big tech companies and AI incumbents might be pursuing regulation with a cynical agenda rooted in the concept of "regulatory capture," a situation where regulatory agencies are dominated by the industries they are charged with regulating. This can lead to regulations that serve the interests of incumbent players, potentially stifling competition and innovation. This strategy, often referred to as "rent-seeking," has been observed in various industries and can manifest in different ways in the context of AI and technology. Three key themes emerge:

Self-Regulation and Influence: Some argue that large tech companies advocate for regulation as a way to shape rules in their favor. By being involved in the regulatory process, they can ensure the rules are more conducive to their business models and create barriers for new entrants.

Stifling Competition: Regulations, especially complex ones, can be burdensome for smaller companies or startups that lack the resources to comply. Larger companies, with more resources and established compliance mechanisms, can navigate these regulations more easily, thus maintaining or increasing their market dominance.

Public Relations: Big tech companies may also push for regulation as a public relations strategy to demonstrate responsibility and address public concerns about AI, even if these regulations primarily serve their interests.

We are seeing some evidence of this phenomenon. We observe significant lobbying efforts by major tech companies in Washington D.C. and Brussels. These companies spend millions on lobbying, suggesting a high level of interest in influencing policy. We also see public statements and testimonies by tech executives advocating for regulation, particularly in areas where it aligns with their strategic interests. Proposals for regulation from tech companies seemingly align with their existing practices or business models, suggesting a degree of self-interest.

This strategy is not new and has been observed in other sectors like the tobacco, pharmaceutical, and finance industries. These industries have historically influenced regulatory frameworks to favor incumbent players, sometimes at the expense of public interest.

The concept of "Big Tobacco" manipulating regulatory processes to its advantage, despite public health concerns, is a classic example.

Many scholars and advocacy groups criticize this approach, arguing that it can lead to regulations that do not adequately address public concerns or the ethical challenges posed by AI. Ironically, Open AI led by Sam Altman and his successor at Y Combinator, Garry Tan find themselves on opposite ends of this argument. Whereas Sam and Open AI, no doubt influenced by their affiliation to Big Tech via Microsoft, Amodei and Anthropic supported by Google previously and now Amazon, advocate for regulation; Garry and influential firms like Andreessen Horowitz and others argue that fostering competition instead of regulation is the way to safely harness the potential of AI.

There's a growing call for regulatory processes to be more independent of industry influence, with a focus on public interest and ethical considerations. Some advocate for regulatory frameworks that support smaller companies and startups, ensuring they are not unduly burdened by regulations designed to rein in larger entities. Through the OECD work and its derivatives, efforts are being made to foster international collaboration on AI regulation, aiming for a more balanced approach that takes into account diverse perspectives and interests

Conclusion

As we delve into the rapidly evolving domain of AI, it's evident that regulatory perspectives are not just necessary but imperative. The global landscape of AI policy and regulation, from China’s proactive stance post-AlphaGo to the nuanced approaches of the OECD, the EU, the US, and India, highlights a common thread: the recognition of AI’s transformative impact on society and the need for governance that balances innovation with ethical and societal considerations.

The OECD AI Principles, the Hiroshima AI Process, the EU AI Act, the US AI Bill of Rights, and India's strategic initiatives all aim to harness AI’s potential while addressing risks. Despite their differences in focus and legal authority, these frameworks share a commitment to inclusive growth, human-centered values, transparency, security, and accountability.

Yet, as AI continues to reshape industries and societies, the question of regulatory capture looms large. The potential for incumbent tech giants to shape AI regulation to their advantage, a practice reminiscent of historical precedents in other industries, underscores the need for vigilance and a balanced approach. Ensuring that AI serves the broader interests of society, rather than just the narrow interests of a few, is a challenge that policymakers, industry leaders, and citizens alike must confront.

In this dynamic environment, my framework offers a structured way to navigate AI’s complexities. By understanding the inherent definitions of AI, its external constraints, and its successful applications, we can better appreciate the multifaceted nature of AI’s evolution and its impact on our world. The journey ahead is not just about technological advancement; it's about shaping a future where AI amplifies human potential and preserves fundamental values.

Take care of yourself,

-abhi